American Poverty: Then & Now, in Words & Images

Eviction: Poverty and Profit in the American City

By Matthew Desmond

Winner of the 2017 Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction

ISBN 978-0553447453

Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing

Photographs at the Oakland Museum of California

runs through August 27th

If you want to understand what’s happening in the American city today, particularly as we struggle locally with the proliferation of homelessness and displacement, there are two lenses through which we can learn more about the experience of poverty. First, Matthew Desmond’s Pulitzer Prize winning book, Eviction: Poverty and Profit in the American City, now in paperback, offers sharp insights as it follows five families as the high cost of rent drives them from poverty into homelessness, and makes them easy prey for “unscrupulous landlords, loan sharks, and credit card companies.”

If you want to understand what’s happening in the American city today, particularly as we struggle locally with the proliferation of homelessness and displacement, there are two lenses through which we can learn more about the experience of poverty. First, Matthew Desmond’s Pulitzer Prize winning book, Eviction: Poverty and Profit in the American City, now in paperback, offers sharp insights as it follows five families as the high cost of rent drives them from poverty into homelessness, and makes them easy prey for “unscrupulous landlords, loan sharks, and credit card companies.”

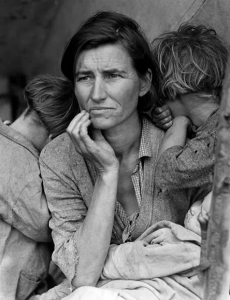

A visual perspective on poverty is on view at the Oakland Museum of California’s “Politics of Seeing” exhibit featuring Dorothea Lange’s haunting portraits of Americans displaced during the Great Depression and the Japanese internment camps. Both Desmond’s book and Lange’s exhibit prompt us to consider how economic hardship is both unfathomable and commonplace, albeit through distinct mediums in different centuries.

In describing the 21st century experience of eviction, Barbara Ehrenreich captures Desmond’s keen sense of the nuance of every day catastrophe in her New York Times review:

“Evictions are scenes of incredible cruelty, if not actual violence. Desmond describes the displacement of a Hispanic woman and her three children. At first she had “borne down on the emergency with focus and energy,” then she started wandering through the halls “aimlessly, almost drunkenly. Her face had that look. The movers and the deputies knew it well. It was the look of someone realizing that her family would be homeless in a matter of hours. It was something like denial giving way to the surrealism of the scene: the speed and violence of it all; gum-chewing sheriffs leaning against your wall, hands resting on holsters, all these strangers, these sweaty men, piling your things outside. . . . It was the face of a mother who climbs out of a cellar to find the tornado has leveled the house.”

— From Barbara Ehrenreich’s review of Evicted

These lines could easily have been written about Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother, a photograph taken in 1936. While Florence Thompson, the woman portrayed in Migrant Mother, was not actually a single mother, her portrait with her children became the recognizable face of poverty and motherhood in the 20th century. Desmond notes that today eviction disproportionately affects single mothers and their children.

In our local context, the book couldn’t be more pertinent as we’ve seen waves of tent encampments swelling in number under each of the city’s overpasses and within public parks.

Migrant Mother by Dorothea Lange, on view at the Oakland Museum of California

What makes it clear that many are recently evicted is the sheer number of personal items that surround each encampment—newly packed cardboard boxes, milk crates, & shopping carts, with tarps covering these belongings beside broken furniture, children’s toys, laundry baskets, and other detritus. A recent glimpse out the car window on 27th Street into a tent through a lowered flap revealed a pressed suit still on its hanger. A tiny potted plant sitting at the edge of a discarded mattress and surrounded by trash marked the boundary of another personal encampment. Even in the direst situations, a sense of maintaining dignity and the concept of home is a strong impulse.

Just a few blocks away at the Oakland Museum of California, 130 stark, black & white images hang on gallery walls in the Dorothea Lange exhibit aptly titled, “Politics of Seeing.” Without Lange’s government-sponsored images, we might not know what abject poverty or injustice looked like during these historic upheavals during the 1930s and 1940s. Seeing stoicism on the faces of Japanese citizens whose belongings were piled on the street as they boarded buses and left their homes for the inhospitable internment camps is a potent reminder of the human dimension of our government policies—and how fear and suspicion towards “immigrants” have very real consequences for families and their livelihoods. Lange never considered herself an artist, instead she aimed to create social change with her photography. Her focus on the harsh reality of the poor and dispossessed gives us an opportunity to recognize our collective humanity, then as now.

Many of us have a tendency to distance ourselves from the plight of those experiencing severe hardship, while simultaneously being aware we are fundamentally no different from those captured in its snare. Given society’s current challenges—climate change, technological displacement, the threat of economic collapse, social injustice, healthcare costs, government corruption—we need to see these as more than just threats affecting those who are less fortunate—any one of us could be swept up in forces beyond our control. Both Desmond’s excellent book and the images in Dorothea Lange’s social commentary inspire us to feel compassion, and hopefully move us closer to action on behalf of those engaged in the struggle already underway.